1878–1922

1816 – 1818 | 1818 – 1878 | 1878 – 1922 | 1922 – 1938 | 1938 – 1945 | 1945 – 1998 | from 1999 |

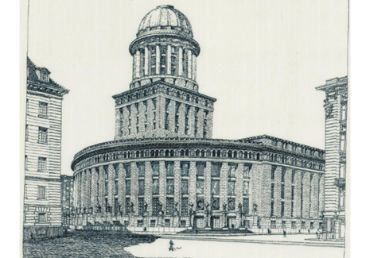

The Austro-Hungarian Bank

Common ground

During the negotiations on the compensation between Austria and Hungary in 1867, the central bank issue was set aside to prevent further complications and to maintain the present conditions until an agreement on a future legal regulation had been reached. Until such a regulation was passed, the central bank was free to exercise its exclusive right of issue in Hungary without restrictions.

After years of prolonged negotiations, in 1878 the central bank was successfully transformed into an institute in which Austria and Hungary had equal shares. The “Austro-Hungarian Bank” became the central bank of both parts of the Empire. The management of the central bank was mainly intent on keeping the governments from encroaching further on its governance, while the governments of Austria and Hungary mainly disagreed on questions of liability for their national debts (at the rate of 80 million florins). The central bank monopoly rights (“Erstes Privilegium”) eventually granted to the Austro-Hungarian Bank represented a compromise between these conflicting interests.

A general meeting and a general council would reflect the unity of the bank administration, but two governing boards and separate head offices in Vienna and Budapest reflected the dualistic nature of the institution.

The Austro-Hungarian Bank needed to undertake far-reaching currency reforms, which included the transition from a silver currency to the gold standard, following a long debate on monetary policy.

After a transitional phase of eight years, the gold crown replaced the silver florin as legal tender in 1900. In everyday business, the new banknotes proved to be a popular currency. Hence, the gold coins backing the banknotes could be locked into central bank’s vaults.

Altogether, the 1880s and 1890s proved to be a successful synthesis of growth and reduction in prices from the bank management’s perspective. Per capita output increased, whereas prices fell or remained stable. These developments made it easier for the central bank to support the banking sector in funding the new boom of industrialization.

The early 20th century

When the central bank monopoly rights were renewed on September 21, 1899 (“Drittes Privilegium”), the autonomy of the Austro-Hungarian Bank was limited somewhat. For example, the state was given the right to access the central bank’s funds under a number of conditions.

At the same time, important changes were made in the central bank’s operational framework, which in effect became the basis for the successful foreign exchange policy of the Austro-Hungarian Bank. This success was evidenced by the fact that the Austro-Hungarian currency stayed on the gold parity until 1914 with very little fluctuation of its external value.

The political developments of the time were crowned with far less success. The conflicts of different nationalities increasingly paralyzed the work of the parliament. Parliamentary elections in 1911 hardly changed the gridlock. In March 1914, the parliament was prorogued. Now, the Stürgkh government ruled without being controlled by parliament. The expansion course which led to the annexation of Bosnia in 1908 was continued, ultimately resulting in the incidents of August 1914.

World War I heats up inflation

The expansionist foreign policy of the Austrian government confronted the management of the central bank with the potential consequences of the forthcoming military conflict. Bank officials were well aware of the fact that the government would primarily resort to the central bank to finance the fast increasing cost of warfare. The management of the central bank had already been compelled to contribute to crisis planning during the crisis in the Balkans in 1912.

Despite its profound skepticism about the optimism of the generals “that considering the state-of-the-art war technology, a war in Europe would surely be over within three months,” the management of the bank was not able to defend the stability of the monetary system.

Just a few days after war had been declared, it became patently clear that the currency would depreciate sharply. The military command ordered that all requisitioned goods should be reimbursed at double their price. After this bombshell of an announcement, inflation was further fueled by a considerable shortage of products and the continuously expanding money supply. During the war, the money supply increased thirteenfold, and the price level rose to sixteen times the peacetime level.

About 40% of the cost of war was financed by the loans of the central bank and about 60% by war loans.

The longer the war continued, the greater the real economic burden for the monarchy became. Decades of efforts to improve productivity were now paralyzed by concentrating resources on the armed conflict. By the time the war was drawing to a close, the real income of workers had been reduced to one fifth of what it had been in the last year of peace.

The breakdown of the old order

What artists and scientists of the fin de siècle had realized well ahead of the general public became clear to everyone by the end of war: The old order had broken down, and coping with the new situation was not easy.

In its search for stable reference points, the central bank encountered considerable problems, mainly because the Imperial and Royal Monarchy fell apart into several successor states from the end of 1918. In spite of the bank management’s efforts to maintain relations with the administrations of each of the recently founded successor states, it could not prevent the currency separation.

As a reaction to the political split, a separate “Austrian management body” was set up. Lacking a reliable guarantee to be able to conduct business independently, the bank’s management was compelled to provide the state with the financial resources needed to cover the immense budget deficit. In the end, the central bank financed about 75% of the federal budget deficit between 1918 and 1922.

After a period in which the crown was massively overvalued, the rates of exchange began to react to the imbalance of the Austrian economy. In the first six months of 1919, the U.S. dollar rose against the crown, jumping from around 16 crowns to nearly 30 crowns. By the end of 1921, the crown had already depreciated to 5,275 crowns to the U.S. dollar. The decrease of the external value went hand in hand with runaway national inflation. The more the value of the crown slipped, the more money was printed. Only the signing of the Geneva Protocol on October 4, 1922, which provided a comprehensive adjustment program supported by a loan guaranteed by the League of Nations, was able to stop the upward trend of prices. But under the terms of the Geneva Protocol, Austria obligated itself to dismiss 100,000 government officials.

The end of the Austro-Hungarian Bank itself had long been foreshadowed. The Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye 1919 provided for the complete liquidation of the Austro-Hungarian Bank as well as other painful provisions for the young Austrian republic. The reparations commission in Paris nominated commissioners, who were charged with executing the entire liquidation while safeguarding the interests of all successor states.

The last ordinary general meeting of the Austro-Hungarian Bank took place on July 14, 1921, and the last meeting of the part of the general council that was responsible for Austria was held on December 15, 1922; it was chaired by Governor Alexander Spitzmüller.